A Disturbance in the Force

Can Customers Prepare for the Coming Round of Protocol Enhancements?

The Internet is quietly being replumbed. That shouldn't surprise

anyone involved with it; the Internet is always being replumbed. But you might

be more surprised to learn that the next

few years will bring an unusual burst of changes in

that plumbing, some with great potential consequences for anyone who

relies on the net.

By "plumbing" I of course refer to the protocols and software that

make the core features of the Internet work. These have been evolving

steadily since 1969, but I don't think any period since the early 80's

has seen as much change as we'll see over the next few years.

Like anything new, these changes will bring both threats and

opportunities, but in this case probably more threats than opportunities. Each

critical part of your infrastructure is potentially at risk from any

fundamental change in the infrastructure, and we are looking at

several such changes in succession.

The Next Big Things

DNSSEC -- For years, experts have warned that the Domain

Name System, one of the most important subsystems on the Internet, is

at severe risk from malicious actors. All sorts of schemes are

possible if you can hijack someone else's domain name, and there are

many ways to accomplish that hijacking. DNSSEC makes domain hijacking much, much

harder, and therefore makes it more reasonable to trust the identities

of Internet sites. It is the foundation for a more trusted net.

After years of work, a milestone was reached in

2010 when the root domain was signed with DNSSEC. Over the next few

years, more and more sites will try to protect their identities and

reputations with DNSSEC. The potential for breaking older or unusual

DNS implementations can't be ignored, but any organization that has a

lot invested in its domain name should consider using DNSSEC to

protect it from hijacking, and to reassure end users.

IPv6 -- The TCP/IP protocols were designed to facilitate

what almost everyone thought was an absurdly big network -- over 4 billion computers. Less than

30 years later, we all know (as I said in 1983, mostly to dismissive laughter) that the 4 billion

addresses enabled by IPv4 are simply not

enough. To keep the net from fragmenting, to facilitate universal

communication, and to avoid having the net's growth stop dead in its

tracks, it is essential that the world convert to IPv6.

Adoption of IPv6 has been slow, but there's a good reason to expect

that to change: halfway through 2011, the supply of IPv4 addresses

will simply run out. There are all sorts of half-measures and hacks

that can postpone things a bit further, but by now it's clear that the

future of the Internet requires IPv6. Despite the many

person-centuries of work that have gone into IPv6, the transition is

highly unlikely to be smooth and painless for everyone.

International email addresses -- For as long as there has been Internet email, addresses have been

limited to the ASCII character set. Spanish speakers can't use the

letter "ñ" even if it's part of their name, and Germans

similarly have to do without their "ö." They've been remarkably

patient with what is, from their perspective, a gross inadequacy in

the email standards. But the people who have it worst, of

course, are the Asians, all of whose characters are forbidden

in traditional email addresses. What people want, of course, are

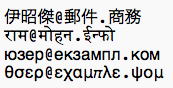

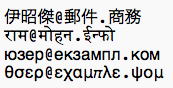

email addresses like these:

After many years of wishing, arguing, and working, the IETF is

closing in on a solution. Internationalized domain names (the right

hand side of the email address) have been a reality for a little while

now, and the IETF has been tackling the final bit, the left hand

side. This turns out to be much, much, much, much, much harder than

it sounds, because of the problem of backward-compatibility with the

old standards and all the old mailers in the world.

The solution is going to be ugly, but functional. New encodings

map ugly strings like "xn--bcher-kva.ch" onto desired

internationalized forms such as "Bücher.ch." Ideally, users will

never see the ugly forms, which are designed to be

backwards-compatible, but inevitably they sometimes will. Worse

still, sometimes it may be impossible for a user of older software to

reply to email from someone with an internationalized address. The

bottom line: we'll be going through a period during which email will

probably not be quite as universal, or as stable, as we're accustomed

to it being. Anyone with responsibility for software that processes

email addresses will need to make sure that their software doesn't do

horrible things when these new forms of addresses are encountered.

DKIM -- The fight against spam is unlikely to ever end,

because the miracle of Moore's Law -- the same miracle that gives us

ever smaller and more powerful computing devices -- operates in favor

of the spammers. Every time we get twice as good at detecting spam,

they are able to generate twice as much spam for the same price, which

means that the good guys are running on a treadmill, needing to work

continuously just to avoid falling behind.

One manifestation of that hard work is the DKIM standard (for

"Domain Keys Identified Mail"), which specifies a procedure by which

organizations can publish cryptographic keys, and sign all their

outgoing mail, thus making it somewhat easier to be sure where some

messages really originate. It's far from a cure-all, but it has the

potential -- particularly when paired with as-yet-undefined reputation

systems -- to make it easier to detect spam with forged sender

information, the issue at the heart of the "phishing" problem. DKIM

has been in development for several years now, and is now progressing

well through the standards process.

DKIM should be mostly invisible to end users, but it will keep mail

system administrators busy for a while. As they learn to configure

their outgoing mail for signatures, and to check their incoming mail

for signatures, there is a strong potential for destabilizing the

email environment in general. The most likely symptom will be mail

that just doesn't reach its intended recipient. That's a much higher

risk during the period that DKIM -- or really, any other anti-spam

standards and technologies -- are being newly deployed.

Reputation services -- High on nearly everyone's list, in

the wake of technologies such as DKIM, are reputation services --

trusted parties that can tell you, if a message is signed as being

from Joe.com, whether or not Joe.com is known for sending spam or

other bad things over the Internet.

Although there are no standards for reputation services yet -- and

although they are undeniably needed -- we can already see the risks

and benefits by looking at the non-standardized reputation services in

use today, notably blacklists of email senders. Although these are

incredibly useful, there is a never-ending stream of problems with

organizations that get added to such lists inappropriately, and the

administrative difficulties of getting them removed promptly.

Similar

considerations will surely apply to the standardized reputation

services of the future -- no such service can be any better than the

support organization that deals with exceptions and problems. Any

progress with reputation standards should be expected to be

accompanied by transitional pains as the reputation service bureaus

mature and develop good or bad reputations themselves.

What Can Customers Do?

Make no mistake: The coming improvements to the Internet's

plumbing are a very good thing. But the implementation of each of

them brings with it the potential for destabilizing various aspects of

the Internet infrastructure, despite the heroic efforts of the IETF to

minimize that risk. Vendors can increase or reduce the risk through

their quality of implementation. What can customers do?

Paradoxically, the answer is to do more by doing less. The biggest

risks are inevitably found in the least professionally administered

software and servers. The big cloud providers with the staff of crack

programmers and administrators are at the least risk, because they

understand the risks well enough to take steps far in advance. But

that specialized application that your predecessor commissioned ten

years ago, and is now running more or less autonomously on an ancient

server in your headequarters, could represent a huge risk.

Basically, the risk is highest where the least attention is being

paid. So the best thing that most organizations can do, in

preparation for the coming instabilities, is to use them as an excuse

to clean house a bit: Decommission old applications that aren't being

maintained, outsource anything you can plausibly outsource to a bigger

IT shop, and allocate a few programming resources to pay attention to

the ones you can't decommission or outsource. Of course, it can't

hurt to ask your cloud provider or outsourcer what they're doing to

prepare for the coming changes, but if they act surprised by any of

them, it may be time to consider a new provider.

Ideally, the coming Internet disturbances should be viewed as an opportunity to streamline some of your oldest, least maintained, most

idiosyncratic infrastructure. In a world where there are

professionals who can run most of your applications for you, locally

or in the cloud, it's probably time for your organization to move

beyond worrying about these kinds of changes. Decommission the old

stuff, outsource whatever you can, and the coming problems will

largely be problems for someone else, not you. And that's about the

best you can hope for as the Internet endures these growing pains.

Last modified: Mon Aug 2 16:52:04 CDT 2010